Benchmarking other organizations, identifying best practices has been a cornerstone of business strategy for decades. It gives us the opportunity to study how others get things done, to learn, and to adapt what we’ve learned into our own organizations.

We benchmark our competitors, their strategies, and products. Or we look at the very high performing companies, the ones scaling outrageously. We study their GTM strategies, their org structures, their programs, and metrics. We put the same things in place for our own organizations.

When we’re considering a new tool, technology, or training program, we typically benchmark it. Vendors point us to reference accounts. We see how well those companies are leveraging the solution, what they’re experiencing. We do the calculations, convinced we can achieve similar results.

But then problems emerge. We aren’t getting the results those we benchmarked are achieving. What was a best practice for another organization ends up being a disaster for others.

We see this everywhere. Two companies choose the same training program. For one, it has a huge impact. For the other, it’s a waste of money. Two organizations choose the same CRM. One leverages it in powerful ways, helping drive real decisions. The other sees incomplete, inaccurate data to the point it’s absolutely useless.

How can organizations doing the same things have such different results?

We Benchmark What We Can See

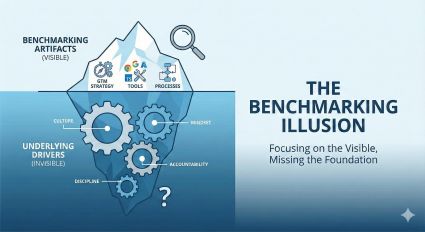

The problem with our benchmarking efforts is that we’re only observing what organizations are doing and how they’re doing it. We can see their org charts and structures. We can see the training they’ve implemented. We can see the technology they’ve deployed. We look at their performance metrics/dashboards.

While we can see all these things, we miss, “How do they make it happen?” It’s the mindsets and behaviors that underlie what they’re doing and how they do it.

Edgar Schein’s work on organizational culture describes three levels: artifacts (visible structures, processes, tools), espoused values (stated strategies and goals), and basic underlying assumptions (the unconscious, taken-for-granted beliefs that actually drive behavior).

Here’s the problem: We benchmark at the artifact level. But the real determinant of success lives at the assumptions level, which is nearly invisible to outside observers.

We adapt the GTM strategies and metrics without understanding why they work? We copy the org chart but not the trust that makes collaboration work. We implement the CRM but not the discipline that keeps data accurate. We adopt the training but not the accountability that reinforces learning.

The Research Is Damning

Jeffrey Pfeffer and Robert Sutton at Stanford coined the term “casual benchmarking” in their research on the knowing-doing gap. They found that companies routinely adopt practices without understanding the underlying logic of WHY they work.

We copy the visible, easy-to-observe elements. We ignore the harder-to-see (and harder-to-implement) foundations.

Their most striking finding? The most commonly benchmarked practices were often the least transferable.

W. Edwards Deming said it bluntly: copying is not adapting. A practice that works brilliantly in one system may fail completely in another because the underlying system is different. You can’t transplant a practice without transplanting the system it operates within. And you can’t transplant a system without transplanting the culture and mindset that created it.

The Strategic Problem

Michael Porter argued that benchmarking for operational effectiveness leads to competitive convergence. Everyone ends up doing the same things. Which eliminates competitive advantage.

But this seems to be the modus operandi in so much of our world today, particularly in SaaS! Too many of the organizations doing the same things, yet not producing the results expected.

If you’re copying best practices, you’re pursuing parity, not differentiation. You’re trying to be better at being the same. In reality, you will always be playing catch-up.

Jim Collins found something similar in his research. Great companies weren’t copying others. They were deeply understanding their own unique intersection of passion, capability, and economic engine. The companies that tried to be like other successful companies, rather than understanding their own uniqueness, consistently failed.

Gary Hamel puts it even more sharply: benchmarking best practices means you’re always following, never leading. By the time a practice becomes a “best practice” worthy of benchmarking, the leaders have already moved on. You’re copying yesterday’s advantage.

What We Should Benchmark Instead

So what’s the alternative? Stop benchmarking entirely?

No. It’s still useful to look at what others are doing. But we need to benchmark different things. We need to ask different questions.

When you visit that reference account, don’t just ask what they’re doing. Ask why it works for them. Ask about the underlying conditions of success for their organization before they could implement it. Ask what they tried that failed. Ask what cultural shifts happened alongside the technology deployment.

Here’s a different way to think about benchmarking:

What mindsets drive their success? That organization getting great results from their CRM, what did they do to get their people to recognize the value of the tool and data accuracy? How did they create accountability? What are they learning about value of transparency in their pipeline? The tool didn’t create those beliefs. The beliefs made the tool work.

What behaviors were non-negotiable? High-performing organizations don’t just have good processes. They have disciplines, things people do consistently regardless of whether anyone is watching. What are the daily, weekly, habitual behaviors that make this practice actually work?

What did they have to stop doing? Every successful implementation required letting go of something. Old habits, competing priorities, comfortable shortcuts. What did they give up to make room for this?

What happens when people don’t comply? This tells you everything about whether a practice is real or performative. If nothing happens when people ignore the process, the process isn’t actually embedded. In any change or initiative, accountability is critical.

How long did it really take? Not how long the implementation took. How long before it became “how we do things here”? Usually much longer than anyone admits publicly.

The Uncomfortable Reality

Here’s what we don’t want to hear: When benchmarking fails, we blame the tool or the practice. “That training didn’t work for us.” “That technology wasn’t right for our situation.”

But the real answer is often harder to accept. The other organization succeeded because of who they are, not what they bought.

They had the discipline to execute fundamentals consistently. They had the accountability to own results instead of making excuses. They had the curiosity to keep learning and adapting. They had leaders who modeled the behaviors they expected.

And you can’t buy any of that. You can’t copy it. It has to be a part of your culture and the way each person operates.

The organization that’s crushing it with their win rates? They were probably already disciplined about curiosity and customer focus. The tools, processes, methodologies provided the platform for consistent execution.

The organization struggling with the same tools, processes, methodologies? They were probably hoping the tool would create the discipline they lacked. It never works that way.

Before You Benchmark, Look In The Mirror

Before your next benchmarking exercise, try this: Assess your own organizational mindsets and behaviors first.

Do you have the curiosity to understand how to make it work within your organization?

Do you have the discipline to execute this practice consistently, even when it’s boring and nobody’s watching?

Do you have the accountability culture where people own results instead of making excuses?

Do you have leaders who will model the behaviors required, not just mandate them?

Do you have the patience to build capability over time, or are you looking for a quick fix?

If the honest answer is no, then then stop! The best practice won’t be best for you. It may be a tragic or expensive mistake.

The most valuable benchmarking insight isn’t learning what high performers do. It’s understanding what high performers are and honestly assessing whether you’re willing to become that.

Benchmarking can be powerful. But only when we stop copying what we can see and start building what we can’t.

Afterword: Here is the AI generated discussion of this post. Enjoy!

Dave, Benchmarking, a universe I inhabited in the 1970’s Mainframe to Mainframe against IBM, then in the 1980’s for distributed Processing and CICS. Tom Peters Promoted ‘swiping’, which IMO never really worked anymore than the excellent companies which FAILED a decade later.

Edgar Schein the Master of Psychology in Business,

we (SALES) would do well to read [or re-read] his opus ‘Humble Inquiry’.

https://www.amazon.com/Humble-Inquiry-Gentle-Instead-Telling/dp/1609949811

Also, those being displaced, or replaced by AI should visit his work on Career Anchors:

“The eight anchors are general managerial competence, technical/functional competence, entrepreneurial creativity, autonomy/independence, security/stability, service/dedication to a cause, pure challenge, and lifestyle.” And, find their NEW PLACE in the AI world.

https://www.amazon.com/Career-Anchors-Revisited-Opportunity-Jossey-Bass/dp/1119899486/22

Great Topic, thank you.

Brian< great references, have them on my reading list.