Any reader who was trained as an engineer or anyone with experience in assembling machines (or Ikea furniture) will recognize the Tolerance Stack Up Error. But, too often, I see the equivalent of this problem in our GTM strategies and execution efforts.

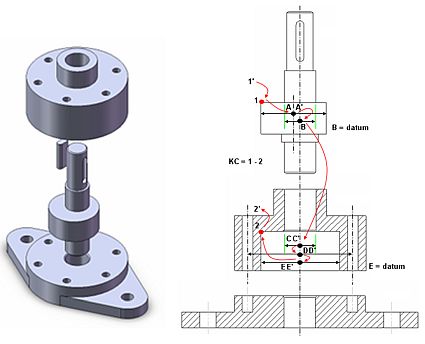

For those of you scratching your heads, let me describe the tolerance tack up error. When we are designing a machine, we specify the dimensions and performance characteristics of each part in the assembly. While we provide exact specifications, “It has to have dimensions of X inches, by Y inches, by Z inches. It has to have a hole of R inches in diameter at this location…..” We specify everything important to the design of the product.

And since we know we are likely to have variance in actually making the product, we specify tolerances we can accept so the product will still meet specifications. For instance if we are producing a part that needs to be 1 inch long, we may specify 1″ +/- 0.1 inches. As long as each part we manufacture fits within those characteristics is deemed a good part and passes the quality control inspection.

But as we start assembling the various parts into a machine or some sort of product, sometimes the aggregation of those tolerances results in something that is out of tolerance. Let’s imagine we need to fill a 6 inch gap with 3 parts. They are specified as Part 1, 1″ +/- 0.1″, Part 2, 2″ +/- 0.2″, Part 3, 3″ +/- 0.3″ Each may be off a little bit, but on average, the idea is they small variances will balance each other out and will fill that 6 inch gap. But sometimes, the small variations, while each is within spec, will cause the entire assembly not to work Imagine the three parts were each at the extreme positive in their tolerance range. The parts would be 1.1″, 2.2″, 3.3″ for an assembled length of 6.6″. While each part is within spec, collectively they won’t fit in the 6 inch gap. It would be 0.6″ too long.

You can imagine all the scenarios, where the variations that are within acceptable tolerances, when put together fail. And the more parts you have to put into the assembly, the greater the problem becomes. Engineers have all sorts of ways to try to minimize this but too often, while each part fits it’s specs, the assembled parts fail. As an aside, much of what we read about the challenges in many Boeing airplanes is the result of tolerance stack up errors on a massive scale. (There are other issues, as well).

So the bottom line, is that while each component of the “system” can be “in spec,” collectively they fail.

We see this everyday in our sales and marketing organizations. Each group may be doing their jobs and meeting their goals. But when it all comes together, the organization is failing to meet it’s goals. Sales enablement is providing high quality training. Sales people are meeting their activity goals, sales ops is doing their reports, managers are managing performance, and so forth. Each part of the organization can be “doing their jobs,” but the organization fails.

- We can imagine sales enablement implementing a new skills development program. At the end of the program, they test the sellers and they have to pass with a certain score.

- Sales managers then set prospecting goals, activity goals, and so forth, holding people responsible for meeting those, “Yes boss, I did my 1000 emails, 100 dials, and 5 demos today…..”

- Sales ops is providing reports on these activity levels, with dynamic reporting systems for real time reporting.

- Marketing even plays a role, they are meeting their goals of a certain number of case studies, product brochures, and references. They are also meeting their MQL goals.

Each is doing their job, yet the organization is failing to reach it’s goals, yet roughly 40% are making their quotas.

Stated differently, we don’t design organizations to achieve roughly 40% of the goal. Whenever I do an assessment of an organization, for the most part, each part of the organization is doing it’s job. But when it all “comes together,” the organization is failing.

What we fail to recognize is that each part of the organization impacts and is impacted by other parts of the organization. Our training dollars are wasted unless management continues to coach and reinforce that training. The fact that we have case studies and brochures isn’t helpful if they don’t address the specific issues our customers face and the sales people know how to leverage them with impact. If sales people don’t know how to engage the customer in the most relevant conversations, the fact that enablement has met it’s product training objectives is meaningless. And if management isn’t understanding and managing the interactions between the pieces/parts of the GTM strategy, the probability is we will fail to achieve our goals.

And when any part of the organization might fail or fall short, this has a ripple effect into the rest of the organization.

For “us” to achieve our goals and to do our jobs, we have to recognize the interdependencies across the organization. We have to recognize, that “doing our jobs,” doesn’t mean the entire organization will be doing it’s job.

The good news, is that if we are making a mechanical product and the parts are out of spec or the assembly doesn’t work, we have to scrap it. Within selling, we can be nimble/agile adjusting things and working with each other to adapt things to meet both our individual organizational goals. We can learn from these experiences optimizing performance across the organization.

Leave a Reply